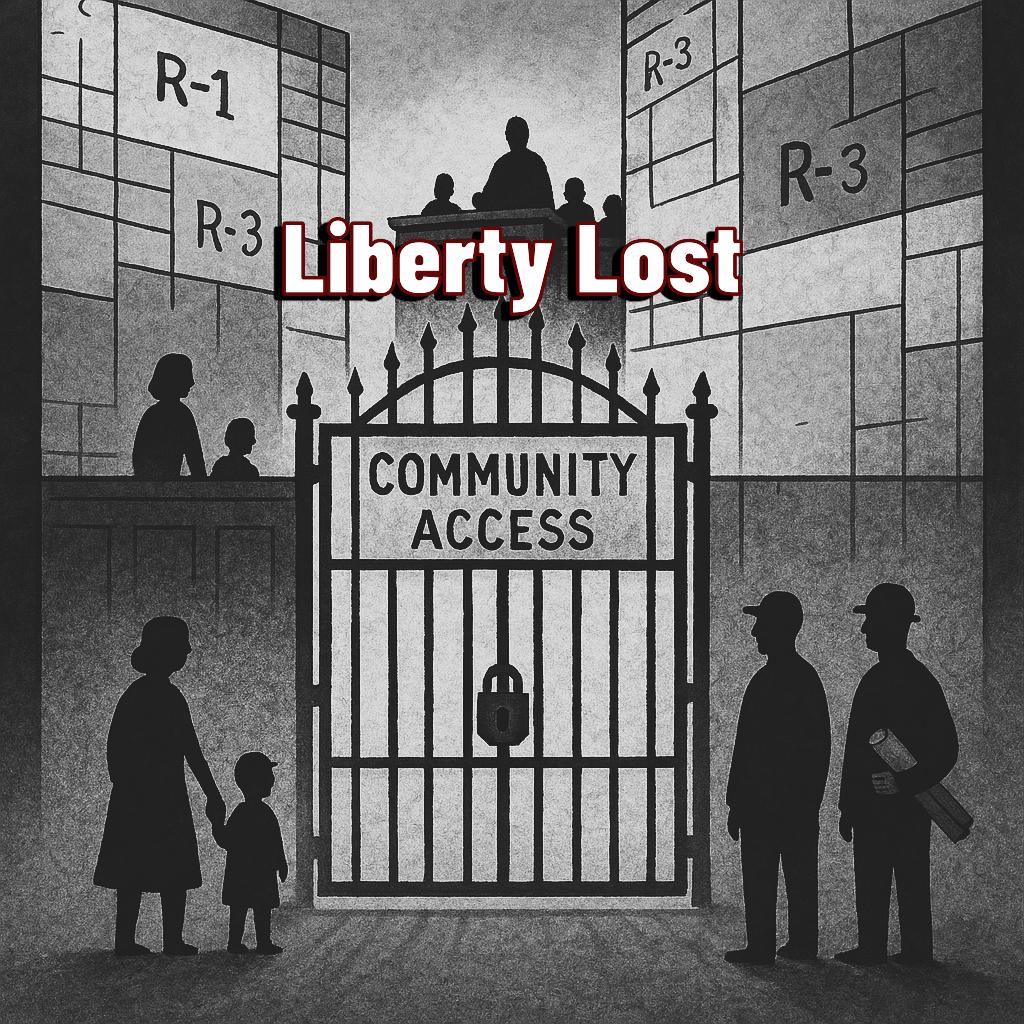

In 1975, the Supreme Court decided Warth v. Seldin, a case that would quietly shape the geography of inequality in America.

The Court handed down a decision that didn’t just miss the mark. It missed the moment.

Warth v. Seldin wasn’t a ruling. It was a retreat.

The plaintiffs didn’t ask for subsidies. They didn’t demand redistribution.

Local governance should be a tool for community flourishing, not a velvet rope for the already privileged.

They asked for access: seeking a door to markets, to opportunity, to the simple dignity of choosing where to live.

And the Court said: You don’t live there, so you don’t count.

That’s not law. That’s ‘interest group’ gatekeeping.

Localism, at its best, disperses power and fosters innovation. But when it’s captured by incumbents, it stops serving people and starts protecting privilege.

In a truly free society, barriers to entry are economic, not political.

But exclusionary zoning is the ultimate protection racket.

It’s a system where incumbents use the state to fence off opportunity and then call it “local control.”

This is central planning in cul-de-sac form, all wrapped up in lawn signs and planning board minutes.

The people most harmed by these policies are too far removed to organize effectively.

They’re treading water just to survive. There’s little time left to thrive.

Meanwhile, the beneficiaries are those who fear “undesirable” neighbors.

Sometimes these “undesirables” are highly motivated, highly vocal, and highly irrational.

It’s the fear of losing out, colliding with not-in-my-backyard defensiveness, slow cooked and seasoned with a pinch of social one-upmanship.

Warth didn’t just uphold zoning. It legitimized a system where incumbents hold the keys to opportunity, caging communities into mono-culture.

But here’s the thing. Communities aren’t clubs.

They are emergent orders.

They thrive when people are free to move, build, and trade.

When we treat housing like a privilege instead of a product of a free market, we don’t just violate liberty. We calcify inequality.

So yes, Warth was about standing. But more profoundly, it was about who gets to stand at all.

And if we’re serious about liberty, we should be serious about tearing down the walls: legal, psychological, and social that keep people out.

Even Ayn Rand, one of my heroes and no friend of redistribution, understood this:

“The smallest minority on earth is the individual. Those who deny individual rights cannot claim to be defenders of minorities.”

Sources for more information:

Leave a comment